Thoughts From The Divide – Schrödinger’s Loss

“A crisis that threatens not just the solvency of office buildings but the loans that are attached to them and the banks that hold them”

While it’s not explicit in our current favorite Twain saying, the reason that “what you know for sure that just ain’t so” is so damaging, isn’t the bad information, but the bad decisions that are based on it. Then there’s Buffet’s famous quote about what happens when the tide goes out and some unfortunate side-effects of “discovery”. In any case, the latest questions surrounding “price discovery” in the office real estate market reminds us of J.K. Galbraith’s famous “bezzle”, or Munger’s “febezzle”. There is a period in which both the embezzler and the embezzled believe they have made money. One of them is wrong but will only find out later: Think of it as “Schrödinger’s loss”.

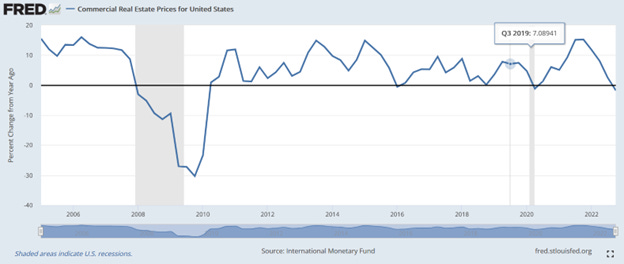

The advantages of “marking to market” in bonds are now much clearer, as are the consequences of allowing banks to use historic cost for “hold to maturity” portfolios. Sadly, plugging one’s ears and saying “I can’t hear you” is not enough to prevent old fashioned bank runs. The danger of collateral repricing is now just as clear in commercial real estate. Take, for example, the fire sale of the 350 California Street office building in San Francisco, where, in addition to the specific evaporation of “roughly 75 percent” of the per-square-foot value of the building (easy come, easy go), one of the articles we cited explicitly mentioned the danger that such a transaction might pose to others hoping to refinance or roll debt due to the repricing, “This could be seen as a bellwether for the value destruction in the urban office market nationally”.

As with “bezzles”, once the illusion fades, the shift in perceived value can lead to a chain reaction, where each new transaction cascades through the system until the market cannot avoid the truth. We appear to be at that stage in the CRE market. Beyond just the ongoing fire sales in major cities, see Baltimore, the tenor of the conversation is changing, with a recent article on the state of commercial real estate in NYC taking a much gloomier tone: “mega-office landlords are panicking, pivoting, and shedding what’s worthless”. As the article notes, landlords are being “forced to reckon with the possibility that the buildings that were worth so much not so long ago may now not even be worth keeping”. On top of the changing status quo around remote or flexible work (“Fridays are ‘dead forever’ and ‘Monday is touch and go’.”), owners are now facing “sharp hikes in interest rates, which make refinancing a huge commercial mortgage a potentially ruinous proposition”. This poses second order threats: “a crisis that threatens not just the solvency of office buildings but the loans that are attached to them and the banks that hold them”. What’s more, the article emphasized that the “slow moving train wreck” could spread out to affect those who rely on public services funded by taxes on those commercial buildings. New York City offices generate, “enormous public revenue… 21% of the city’s property-tax levy – money that goes to pay for schools, public housing, fire trucks, pensions, parks, and so much else that makes life in New York tolerable”. (Tolerable, eh?)

Of course, neither the building owners nor their bankers are in any hurry to open the valuation box and find out whether “Schrodinger’s cat” is alive or dead for financing purposes. “At the moment, because there are few transactions outside distress sales, it’s hard to calculate a building’s underlying value.” Is ignorance bliss? No, but it’s better than certain default.