“Forced to make extensive changes after… plans were blown off course”

A little less than two years ago, we noted, with some surprise, that Huw Pill had bucked the usual central bank modus operandi of avoiding unfortunate truths and had instead gone the direct route, telling the UK “we’re all worse off, and we all have to take our share”. Speaking about inflation, the BoE’s Chief Economist clarified that, “If the cost of what you’re buying has gone up compared to what you’re selling, you’re going to be worse off… So somehow in the U.K., someone needs to accept that they’re worse off and stop trying to maintain their real spending power by bidding up prices”. No good deed (if blunt honesty about painful truths counts) goes unpunished, as Mr. Pill made abundantly clear with profuse apologies for his tasteless candor. However, putting aside aberrations of protocol, it’s the subject of the sentence above, “someone”, that has caught our attention this week. In the official sector this is often referred to as “burden sharing”: establishing exactly who it is who will bear the brunt. With both public and private sectors experiencing tougher times, it’s natural that there’s significant jockeying to decide just who exactly is going to bear the brunt.

Of course, sometimes there is so much pain to go around that everyone gets a slice. Consider Japan, where the price of rice has become a highly contentious issue, much like the sensitivity to gasoline prices in the US. Like the US and oil, the Japanese government maintains a strategic reserve of rice, which it felt compelled to release to combat elevated prices. Despite the government release, rice prices “were up 81 percent year-on-year – a record for the grain” in February. This meant that while Japan’s core inflation slowed slightly, to 3.0% from 3.2% in January, the BoJ felt obliged to comment. “Rising food costs are usually seen as supply shocks that can be overlooked. However, the prolonged increase in rice prices means the risk of these rises affecting inflation expectations and public sentiment is not negligible.” For more on this idea, we’d refer readers to our discussion of Adam Tooze’s eureka moment: that there’s a difference between official and felt inflation, and at least some of it reflects the lack of substitutability.

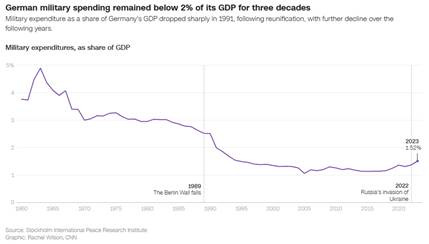

The Europeans are also facing difficult decisions regarding who must foot the bill. Their new-found interest in re-industrialization (specifically military) is obviously expensive but also obviously, potentially quite lucrative for business. As this article on Germany’s latest push notes, 66% of respondents in a survey conducted by a German broadcaster “believe it’s right to increase spending on defense and the Bundeswehr”, the country’s armed forces. The survey additionally “found that 59% of those surveyed agreed that Germany should significantly increase its debt in order to ‘cope with upcoming tasks, especially in defense and infrastructure’”. As an aside, just because you have a fresh stack of bonds for sale, doesn’t mean that you’ll find happy and willing buyers at prior market clearing yields. A point which is clearly not lost on Southern Europeans.

In the UK, the rubber is already meeting the road in the push for defence spending as the latest from Madame Reeves includes a “further £2.2bn for defence, while a target has been set to reduce the administrative costs of government departments by 15% by 2030.” Admittedly, the fact that the UK’s military is currently only fit for deterring the French, is a known known (h/t “Yes, Minister”). But when the British ask “for whom the bell tolls”, they already know the answer. Reeves has “insisted… that she was determined to keep a grip on the public finances”. “People should have no doubt about my commitment and how seriously I take the fiscal rules, as I said today, they are non-negotiable”. We’d of course refer Rachel from Accounts to the great philosopher, Mr. Mike Tyson, but in the meantime, a girl can dream.

While these European projects all come with a hefty price tag and the ensuing question of where the money is going to come from, perhaps the answer is implicit in “Liberation Day”. While Trump had used the phrase in his inaugural address, he has since used the term to refer to April 2, the day that the Administration will begin to impose “fair, reciprocal tariffs” on a broad swath of countries.

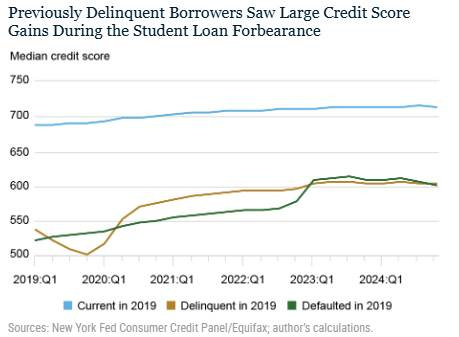

P.S. We’re broadly suspicious that the DOGE campaign and other Trump Administration programs are net withdrawals of fiscal stimulus, and this Tweet from Bloomberg economist Anna Wong highlights the double-edged nature of this… What happens when there’s a “sudden repricing of risk” AND people suddenly need to start paying student loans?

Things Are Changing. Fast.

This is when macro thinking stops being optional — and starts being essential. Subscribe now.